Published on January 31, 2024

Fortunately there are alternative approaches that could be used and that have clear parallels in other fields of medical physiology

Key Points

- We say an engine is running normally if it is doing what it was designed to do, it does so without various kinds of hiccoughs, and it doesn’t break down prematurely. In theory the same concept should apply to nutrition, where “normal” would mean getting enough of all nutrients to allow our various organs and systems to run the way they were designed and to continue to run smoothly for as long as possible – unfortunately, while we know what a mechanical device is designed to do, we don’t have the same assurance when it comes to our physiology.

- An “adequate” (or normal) nutrient intake is the intake, above which further increases produce no further benefit to the individual – long-term or short-term; this is conceptually straightforward, but hard to establish empirically for reasons discussed here

- Using the ancestral intake criterion of “normal”, one might formulate a contemporary recommendation for vitamin D as a target serum concentration of 25(OH)D in the range of 40–60 ng/mL (100–150 nmol/L); recent dose response studies show that achieving and maintaining such a level typically requires a daily input, from all sources combined, of 4000–5000 IU vitamin D

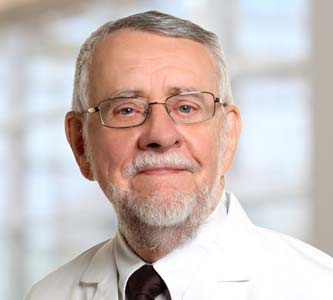

Written by Robert P. Heaney, M.D.

Written by Robert P. Heaney, M.D.

You might think that the idea of “normal” would be pretty straightforward. We say an engine is running normally if it is doing what it was designed to do, it does so without various kinds of hiccoughs, and it doesn’t break down prematurely. In theory the same concept should apply to nutrition, where “normal” would mean getting enough of all nutrients to allow our various organs and systems to run the way they were designed and to continue to run smoothly for as long as possible.

Unfortunately, while we know what a mechanical device is designed to do, we don’t have the same assurance when it comes to our physiology. We don’t have an owner’s manual to consult. Instead, we try to find individuals in the population who appear to be healthy, assess how much of various nutrients they ingest, and consider such intakes to be adequate (i.e.,“normal”). After all, they’re “healthy”. That seems sensible on the surface, but it is inherently circular because it begs the question of “normal”. While such individuals may not be exhibiting recognized signs of nutritional deficiency, that certainly does not mean that current intakes are optimal for long-term physiological maintenance. (A parallel is the regular changing of the oil in our cars which has no immediately apparent effect, but certainly has consequences for the future of the engine). If, as seems increasingly likely, there is a causal role played by inadequate nutrient intake in the chronic degenerative diseases of aging, then we need to find a better way to assess what is “normal”.

It’s important to understand that “normal” in this sense does not mean that a person with an adequate intake thereby has “optimal” health. Nutrition is terribly important, but it is certainly not the only determinant of health. By contrast, an “adequate” (or normal) nutrient intake is the intake, above which further increases produce no further benefit to the individual – long-term or short-term. That’s conceptually straightforward, but hard to establish empirically. Of the many difficulties I might list are: 1) The harmful effects of an inadequate intake may not be apparent until later in life; as a result the requisite studies are generally unfeasible; 2) We may not know what effects to look for even if we could mount such a study; and 3) The required evidence can come only from studies in which one group would be forced to have an inadequate (i.e., harmful) intake, which is usually ethically unacceptable. Not being able to confront these difficulties head-on, we fall back to presuming that prevailing intakes are adequate and we shift the burden of proof to anyone who says that more would be better. (“Better” here means, among other things, a smaller burden of various diseases later in life, an outcome which, as just noted, may not be easily demonstrable.)

Fortunately there are alternative approaches that could be used and that have clear parallels in other fields of medical physiology. In this post I address one of these: ancestral intake.

It’s important to recognize two key points: 1) Nutrients are substances provided by the environment which the organism needs for physiological functioning and which it cannot make for itself; and 2) The physiology of all living organisms is fine-tuned to what the environment provides. This latter point is just one aspect of why climate change, for example, can be disastrous for ecosystems since, with change, the nutrients provided by the environment may no longer be adequate. Thus, knowing the ancestral intake of human nutrients provides valuable insight into how much we once needed in order to develop as a species.

It’s helpful to recall that humans evolved in equatorial East Africa and during early years there (as well as during our spread across the globe) we followed a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. During those millennia populations that found themselves in ecologic niches that did not provide what their bodies actually needed, simply didn’t survive. The ones that did survive – our ancestors – were the ones whose needs were matched to what the environment provided. The principles of Darwinian selection apply explicitly to this fine-tuning of nutrient intakes with physiological functioning.

Thus knowing how much protein or calcium or vitamin D or folate our pre-agricultural ancestors obtained from their environments gives us a good idea of how much might be optimal today. There is no proof, of course, that an early intake is the same as a contemporary requirement, because many other things besides diet have changed in the past 10,000 years. But since we have to presume that some intake is adequate, it makes more sense to start, not with what we happen to get today, but with the intake we can be sure was once optimal. The burden of proof should then fall on those who say that less is safe, not on those who contend that the ancestral is better than the contemporary intake.

How do we know what the ancestral intake of many nutrients might have been? Certainly, in some cases, we don’t know, and this approach, therefore, might not be possible for such nutrients. But, surprisingly, we do have a pretty good idea about the primitive intake of many nutrients. And when we have the data, why not use what we do know for those nutrients?

There are not very many populations today living in what we might call the ancestral lifestyle, and often they are in marginal habitats which may not be representative of what early humans experienced. But that has not always been the case. Over the last 150 years there has been extensive, world-wide, ethnographic study of native populations with particular emphasis on those who have come into stable equilibrium with their environments. There are reams of data with respect to dietary intakes reposing in various libraries and museums, remarkably comprehensive, and shedding priceless light on the habits and status of people we can no longer know or experience first-hand.

Take vitamin D as just one example. We know that proto-humans in East Africa were furless, dark-skinned, and exposed most of their body surface to the sun, directly or indirectly, throughout the year. We know how much vitamin D that kind of sun exposure produces in the bodies of contemporary humans, both pale and dark-skinned, and we have made direct measurements of the vitamin D status of East African tribal groups pursuing something close to ancestral lifestyles. We know also that, as humans migrated from East Africa north and east, to regions where sun exposure was not so dominant, and where clothing became necessary for protection from the elements, skin pigmentation was progressively lost, thereby taking better advantage of the decreased intensity of UV-B exposure at temperate latitudes and enhancing the otherwise reduced vitamin D synthesis in the skin.

All of these lines of evidence converge on a conclusion that the ancestral vitamin D status was represented by a serum concentration of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D (the generally agreed indicator of vitamin D nutritional status) in the range of 40–60 ng/mL (100–150 nmol/L). Recent dose response studies show that achieving and maintaining such a level typically requires a daily input, from all sources combined, of 4000–5000 IU vitamin D.

Thus, using this ancestral intake criterion of “normal”, one might formulate a contemporary recommendation for vitamin D nutrient input somewhat as follows:

“We don’t know for certain how little vitamin D a person can get by on without suffering health consequences, but we do know that our ancestors had an average, effective intake in the range of 4000–5000 IU/day. We also know that this intake is safe today. Thus we judge that the most prudent course for the general population is to ensure an all-source input in the range of 4000–5000 IU/day until such time as it can be definitively established that lower intakes produce the same benefits.”

About Dr. Robert P. Heaney

Dr. Heaney was a full time professor at Creighton University who also donated his time and energy, starting in 2012 until his passing in 2016, as Research Director at GrassrootsHealth. In this capacity Dr. Heaney consulted on studies, methodologies, and how to best change public health direction. Dr. Heaney provided nearly 50 years of advancements in our understanding of bone biology, osteoporosis, and human calcium and vitamin D physiology. He is the author of three books and has published over 400 original papers, chapters, monographs, and reviews in scientific and educational fields. At the same time, he has engaged nutritional policy issues and has helped redefine the context for estimating nutrient requirements. Dr. Heaney was presented a lifetime achievement award in the US House of Representatives on November 10, 2015 (Watch the video here). He was an inspiration to researchers everywhere – his intellect, dedication, integrity, and caring was unsurpassed.

Dr. Heaney was a full time professor at Creighton University who also donated his time and energy, starting in 2012 until his passing in 2016, as Research Director at GrassrootsHealth. In this capacity Dr. Heaney consulted on studies, methodologies, and how to best change public health direction. Dr. Heaney provided nearly 50 years of advancements in our understanding of bone biology, osteoporosis, and human calcium and vitamin D physiology. He is the author of three books and has published over 400 original papers, chapters, monographs, and reviews in scientific and educational fields. At the same time, he has engaged nutritional policy issues and has helped redefine the context for estimating nutrient requirements. Dr. Heaney was presented a lifetime achievement award in the US House of Representatives on November 10, 2015 (Watch the video here). He was an inspiration to researchers everywhere – his intellect, dedication, integrity, and caring was unsurpassed.

Read more about Dr. Heaney and a few of his accomplishments here.

How Are Your Levels of Important Nutrients?

Do you know what your vitamin D level is? Check yours along with omega-3s, magnesium, and other levels today as part of the vitamin D*action project; add the Ratios for more about how to balance your Omega-3s and 6s!

Measure your:

- Vitamin D

- Magnesium PLUS Elements

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids

- hsCRP (for Inflammation)

- HbA1c (for Blood Sugar)

- and more

Did you know that each of the above can be measured at home using a simple blood spot test? As part of our ongoing research project, you can order your home blood spot test kit to get your levels, followed by education and steps to take to help you reach your optimal target levels. Start by enrolling and ordering your kit to measure each of the above important markers, and make sure you are getting enough of each to support better mood and wellbeing!

Build your custom kit here – be sure to include your Omega-3 Index along with your vitamin D.

Start Here to Measure Your Levels