Published on August 15, 2022

How have you and those around you responded to the latest interpretation of the VITAL trial on fracture rates? Here is the last of our 3-part response for you to share with others.

Key Points

- Is 2000 IU/day enough? For the LeBoff et al. study participants whose vitamin D level was measured throughout the study (2,655 participants out of 23,216), 2,000 IU/day was enough to increase the average serum level from 29 ng/ml to 41 ng/ml (meaning nearly half of those with follow up vitamin D levels were still below the recommended 40-60 ng/ml)

- The hypothesis of vitamin D research should be that increased vitamin D levels into the therapeutic range, not the dose amount, will produce the specified effect (less disease, reduced symptoms, etc.); since vitamin D synthesis varies greatly for each person, the hypothesis cannot be by treatment amount (supplement intake) but instead needs to be investigated around achieving a certain serum level

- Co-nutrients are nutrients that work together for some process; if one co-nutrient is limited, either missing or not plentiful enough, then the process might also be limited or not able to take place at all

The latest publication using data from the VITAL trial by LeBoff et al., titled “Supplemental Vitamin D and Incident Fractures in Midlife and Older Adults,” concluded that vitamin D supplementation did not reduce the risk of fracture compared to placebo among their study population, and the publicity that followed prompted many to question the usefulness of vitamin D in general.

The latest publication using data from the VITAL trial by LeBoff et al., titled “Supplemental Vitamin D and Incident Fractures in Midlife and Older Adults,” concluded that vitamin D supplementation did not reduce the risk of fracture compared to placebo among their study population, and the publicity that followed prompted many to question the usefulness of vitamin D in general.

In our first post addressing these findings, we introduced several study criteria that should be followed when designing and analyzing nutrient research. Our second post explained key concepts that support why these criteria are essential, especially for vitamin D research, followed by whether the LeBoff paper met 2 of the 5 criteria. Today, as we review the remaining 3 criteria, we hope to help everyone gain a better understanding of why the results from this publication may actually be expected based on the study design. More importantly, using the findings from this study to suggest that vitamin D is not helpful for bone health and fractures (or even health in general), as the publicity following the paper suggested, could lead to detrimental consequences and is an example of how poorly designed vitamin D research, and the interpretation of it, can be a major disservice to public health.

Did the LeBoff Paper Meet Nutrient Study Criteria #2, 4 and #5 when Analyzing for Bone Fractures?

Let’s take a look at the remaining nutrient study criteria to see if they were met.

Criteria #2: The intervention (i.e. change in nutrient exposure or intake) must be large enough to change nutrient status and must be quantified by suitable analyses.

QUESTIONNABLE

To determine if an intervention (dose of vitamin D) is great enough to have a specific effect (change in vitamin D level), baseline and follow-up levels must be measured. All participants in the intervention group were given the same dose of vitamin D (2,000 IU per day), however, not all participants’ baseline and resulting vitamin D levels were measured to see how this dose affected their vitamin D level and if it got them to the ‘therapeutic’ range of 40-60 ng/ml (100-150 nmol/L).

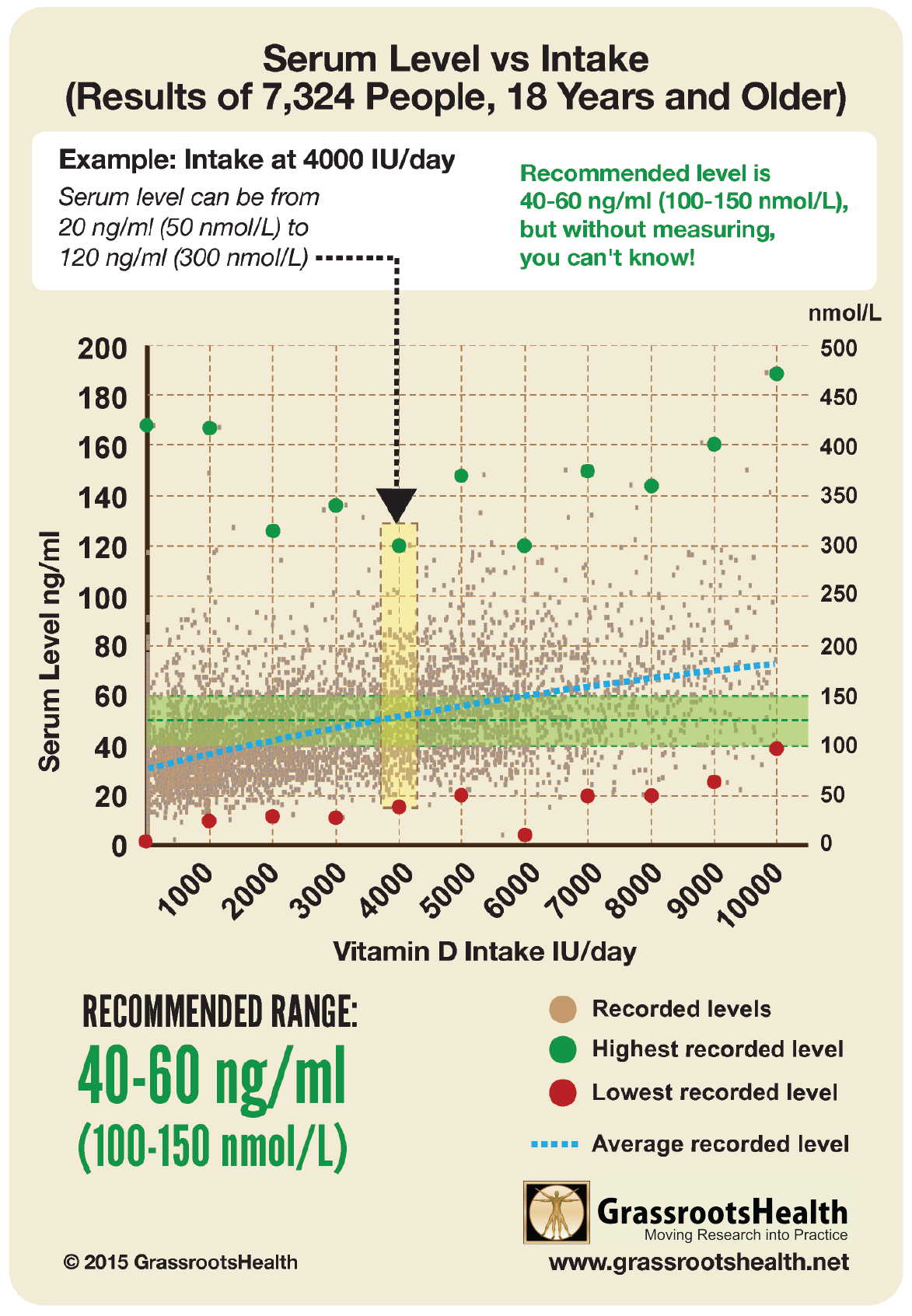

Is 2000 IU/day enough? For the study participants whose vitamin D level was measured throughout the study (2,655 participants out of 23,216), 2,000 IU/day was enough to increase the average serum level from 29 ng/ml to 41 ng/ml (meaning nearly half of those with follow up vitamin D levels were still below the recommended 40-60 ng/ml). This is similar to findings from the GrassrootsHealth cohort, which showed that 55% of participants taking 2,000 IU/day achieved a level of 40 ng/ml or higher, which leaves 45% of participants below that target level. A detailed breakdown of vitamin D levels by intake can be seen in the chart here.

Remember – One Dose does Not Fit All

Everyone responds differently to vitamin D… by up to 6 times for the same supplement amount!

Certain factors can influence how an individual’s vitamin D level responds to their vitamin D supplementation amount (called the dose-response). These factors can cause a wide range of serum level responses that can be produced when looking at any specific supplementation amount. For example, it is possible for a supplemental intake of 4000 IU/day to result in a serum level of 25 ng/ml (62.5 nmol/L) in one individual, and 60 ng/ml (150 nmol/L) in another – making measuring the resulting vitamin D level essential to knowing whether an individual is getting an appropriate dose or if that dose needs to be adjusted.

Criteria #4: The hypothesis to be tested must be that a change in nutrient status (not just a change in intake) produces the sought-for-effect.

DID NOT MEET

The hypothesis should be that increased vitamin D levels into the therapeutic range, not the dose amount, will produce the specified effect (less disease, reduced symptoms, etc.). This premise is often the core problem; since vitamin D synthesis varies greatly for each person, the hypothesis cannot be by treatment amount (supplement intake) but instead needs to be investigated around achieving a certain serum level.

All analyses in the LeBoff paper, including sub analyses that did consider baseline vitamin D levels, only made conclusions based on change in intake (whether they were in the vitamin D group or the placebo group), not based on change in nutrient status or vitamin D level achieved. Also, since the average starting vitamin D level in both groups was over 30 ng/ml, which is already considered sufficient for bone health, increasing vitamin D levels would not be expected to have an additional effect on fracture rate (as explained in detail in Part 2).

Very Clear Difference in Findings when Comparing Achieved Serum Level vs Dose Given

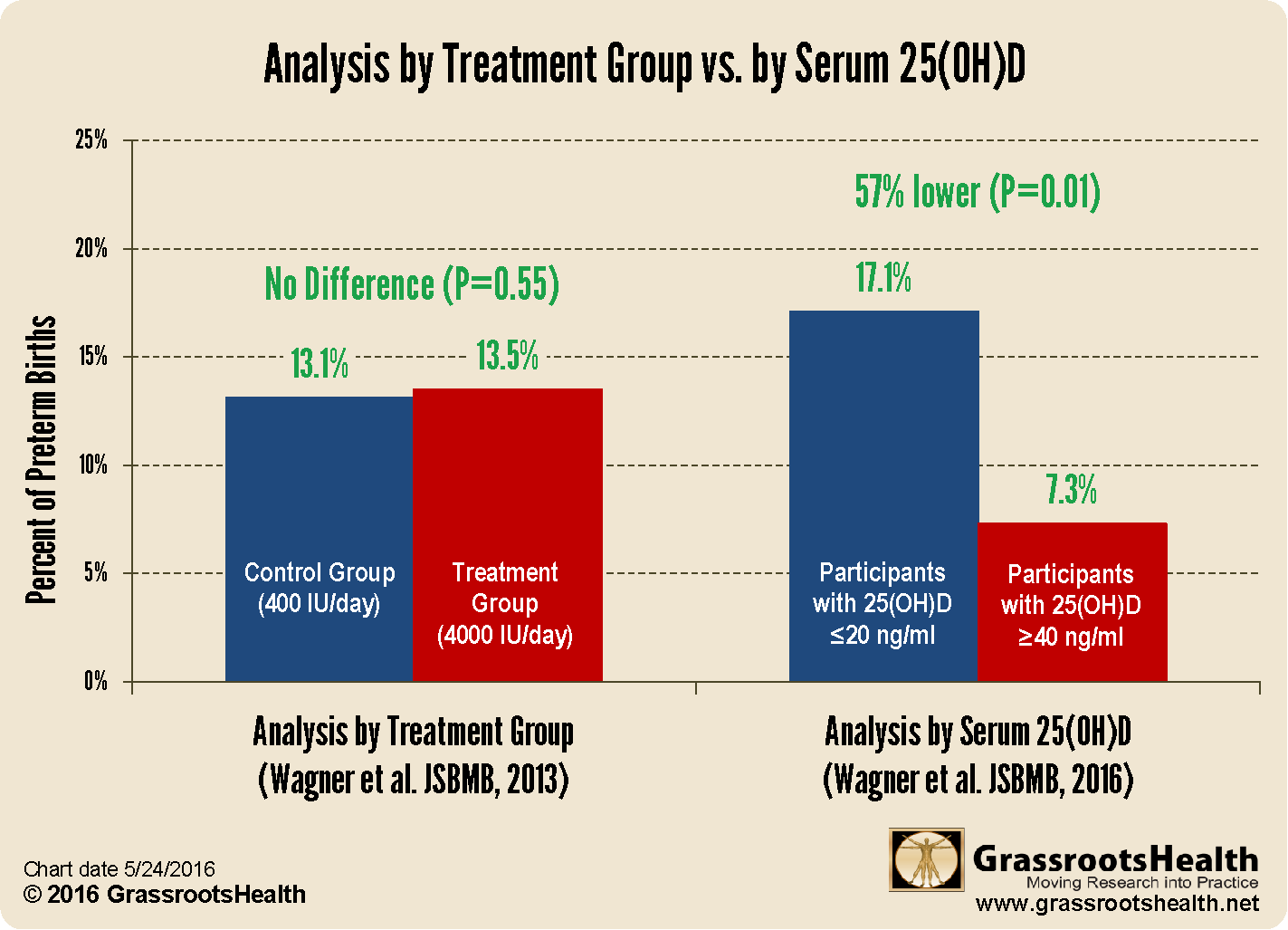

We have seen this mistake made over and over again with trials that associate findings with a dose instead of an achieved vitamin D level. An example of the difference in findings is the Wagner et al. study on preterm birth, which when re-evaluated by serum level instead of dose, found a much different, positive benefit for vitamin D.

As can be seen here, there was no difference when the data was analyzed by dose of vitamin D given. When we look at the same data by achieved vitamin D level, there is a very large, significant, positive difference.

Criteria #5: Co-nutrient status must be optimized in order to ensure that the test nutrient is the only nutrition-related, limiting factor in the response.

DID NOT MEET

Co-nutrients are nutrients that work together for some process. If one co-nutrient is limited, either missing or not plentiful enough, then the process might also be limited or not able to take place at all. While this criteria is not a reason to throw out a study, it would be optimal to optimize co-nutrients to more clearly define the effect of the nutrient in question.

Several nutrients are essential for bone health, including calcium, magnesium, vitamin K, and others. While the LeBoff paper did seem to track calcium intake outside of the study, the effort was not made to ensure adequate calcium intake for all participants, and there was no mention of any other co-nutrients that are important for bone health.

How do Co-Nutrients Work Together for Optimal Health Outcomes?

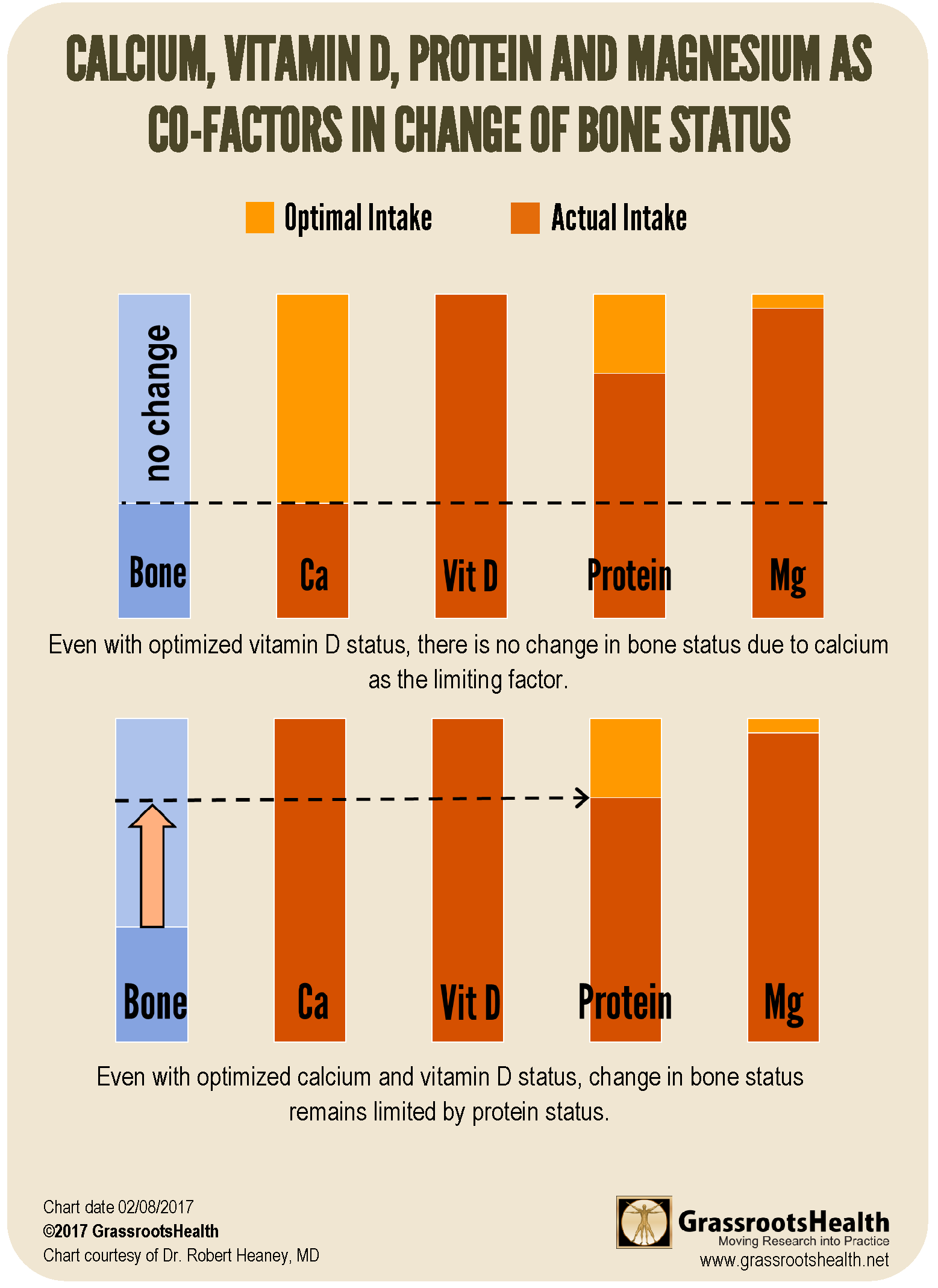

The following charts illustrate how co-nutrient status can affect a target outcome such as bone status.

In the charts, each nutrient is at optimal status when its bar is full (dark orange). When any or all nutrients are below the optimal level (leaving the lighter orange showing), bone status is impaired at the level of the lowest, or most limited, nutrient. If one were to focus on optimizing vitamin D, without also optimizing calcium, protein, and magnesium (such as in the top chart), no change in bone status would be observed, leading to a false conclusion that vitamin D does not affect bone status. Even if calcium and vitamin D status are optimized, as shown in the bottom chart, bone status would improve but would still be limited by the protein status. Because the nutrients interact in the maintenance of bone health, the effects of a single nutrient may be overlooked if intake of others is not sufficient.

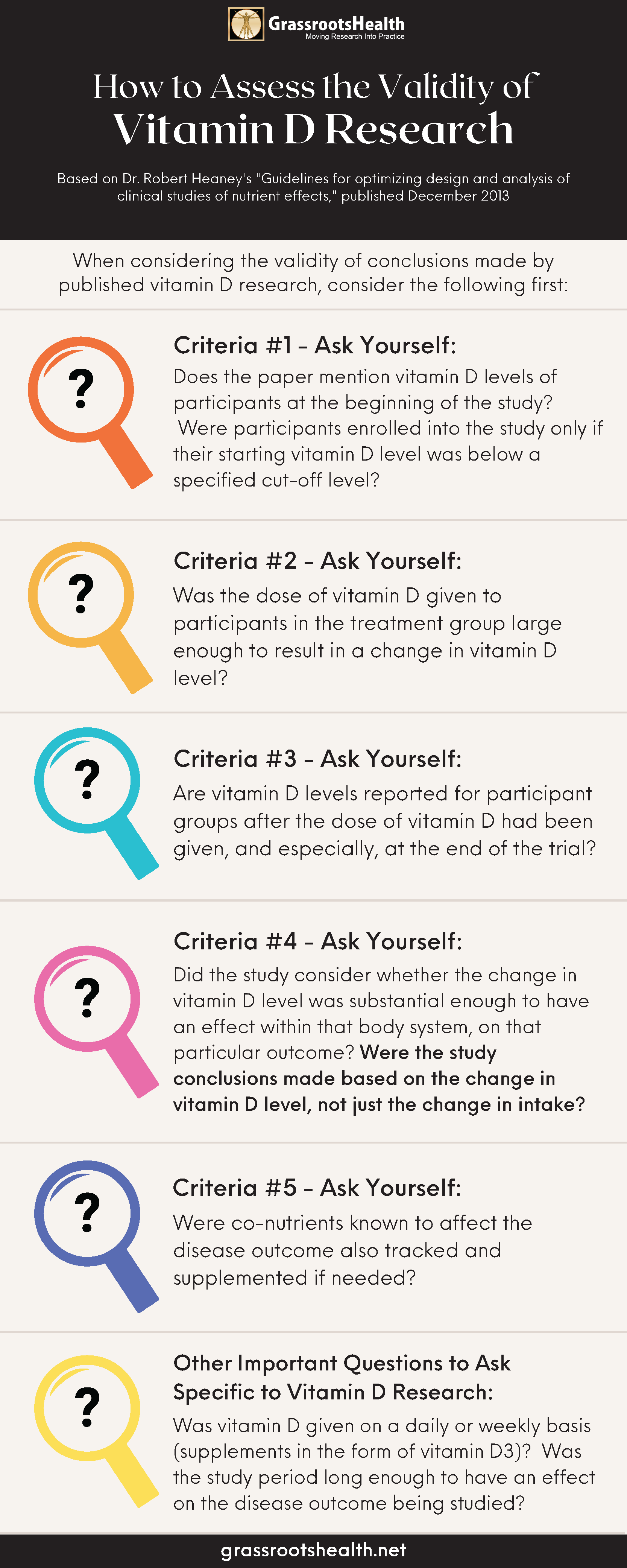

Remember Dr. Heaney’s Nutrient Study Criteria when Considering the Validity of Vitamin D Research

Hopefully, these 3 posts have created a better picture of how to approach published nutrient research, using Dr. Heaney’s nutrient study criteria, to determine for yourself what amount of validity the study conclusions hold. While there is a bit more to consider along with these criteria specific to vitamin D research, the infographic below is a good general guide and reminder of what to look for.

Vitamin D is an Easily Modifiable Factor to Help Improve Disease Outcomes – What Vitamin D Level do YOU Have?

Don’t ever consider a situation too late to take steps for correcting or avoiding vitamin D deficiency. Measuring your vitamin D level and calculating a supplementation amount to help reach and maintain a target level, or taking loading doses to correct deficiency faster, could possibly make all the difference in how a current disease situation progresses. Test your level now!

Create your custom home blood spot kit by adding any of the following measurements, along with your vitamin D:

- Omega-3 Index (with or without Ratios)

- Magnesium (with or without additional Elements – copper, zinc, selenium, mercury, cadmium, lead)

- hsCRP as a marker of inflammation and HbA1c as a marker of blood sugar health, two other important factors influencing prenatal conditions

Having and maintaining healthy vitamin D levels and other nutrient levels can help improve your health and the health of your baby, now and for the future. Enroll and test your levels today, learn what steps to take to improve your status of vitamin D (see below) and other nutrients and blood markers, and take action! By enrolling in the GrassrootsHealth projects, you are not only contributing valuable information to everyone, you are also gaining knowledge about how you could improve your own health through measuring and tracking your nutrient status, and educating yourself on how to improve it.